Strunjan peninsula

The natural attributes of the Strunjan Peninsula, its Mediterranean climate and lee position in particular, have enabled the population of this area and the development of traditional economic activities in harmony with nature.

Dispersed settlement, terrace farming, an inshore fishery and artisanal salt-making have moulded a cultural landscape characterised by a variety of living and cultural environments.

History and Development

The earliest evidence of the settlement of the Peninsula of Strunjan dates back to antiquity and has been discovered in the areas of St. Bassus and Cape Ronek: a Roman villa rustica (a countryside villa, often the hub of a large agricultural estate), piers of an ancient port, now submerged due to the gradual sea level rise throughout the centuries, and individual smaller architectural remains.

The area was first mentioned in archival sources in the 11th century, when the Patriarch of Aquileia Poppo of Treffen donated it to the Benedictine convent of St. Mary in Aquileia. The place name Strugnano, was first entered into official documents in 1284, and is believed to originate from the Latin word Stronnianum, meaning Stronnio’s. In the 4th and 5th centuries, in fact, it was customary for territories to be named after owners of the largest local estates, so it can be assumed that Stronnianum used to be the designation of a property owned by a person named Stronnio. And, eventually, from the medieval Italian toponym the Slovene derivative Strunjan developed.

Throughout history, the town evolved in close interrelation with neighbouring Piran. While the latter grew from a late antiquity settlement into a typical medieval centre, Strunjan remained, thanks to its climate perfect for salt-making and its fertile land ideal for the cultivation of field and garden crops, fruit, olive trees and vine, Piran’s steadfast natural economic hinterland.

During the years of Trieste’s greatest prosperity in the late 18th century and up until the end of WWII, agriculture was the key economic activity of this area. The farmers of Strunjan for the most part carried their products to the markets of Trieste by boat – mostly early yield from their gardens and orchards, which cropped heavily in the microclimate of the sunny plots and terraces. Later, they focussed more on olive oil, wine and persimmon production, and in more recent years on artichoke growing and mussel farming in the coastal area.

The economic situation of the town, which was dependent on the port of Piran for large transports, changed radically in the beginning of the 20th century with the construction of the Trieste-Poreč narrow-gauge railway line, which made a stop in Strunjan. The new, more convenient land links fostered the progress of the entire Istrian Peninsula, but in particular of the inland, higher areas, which had previously been virtually cut off from the coastal towns. In this period, several villas and guesthouses were built in Strunjan. Although the Trieste-Poreč line was discontinued in the early 1930s, the construction of various tourist facilities in the town continued, with motor vehicle traffic superseding the railway system, and progress being spurred on by the reinvigorated tourism in the neighbouring town of Portorož.

A turning point in the development of Strunjan and its surroundings was the designation of the area as a landscape park following ordinances passed by the Izola and Piran municipalities in 1990, and the subsequent placement of the park under state-level protection in 2004. Landscape Park Strunjan was founded with the objective of promoting sustainable development that would be in line with natural value protection, as well as preservation of biological and landscape diversity, while not hampering the prospects of development for the population of the area.

Pine tree Avenue

Upon the construction of the main Koper-Izola-Portorož stretch, pine trees were planted alongside, creating over the years a stone pine avenue of around 110 trees, their crowns touching to create a veritable tunnel, the longest and best-preserved in Slovenia. In 2004, it was declared a natural monument, part of Landscape Park Strunjan.

If you had stood on this spot between 1930 and 1940, you would have seen the Strunjan Valley on its way to gradually taking the shape it has today. In 1935, the railway line Parenzana, which had passed through Strunjan for three full decades, was shut down and the role of connecting the littoral towns with the Istrian hinterland was taken over by roads.

Interesting Facts

- Stone pine (Pinus pinea) is, relatively, not a long-lived tree species, as it rarely exceeds the age of 150 years. It can grow up to 25 m in height.

- Man has been planting stone pine for its edible seeds (called pine nuts) for at least 6,000 years. The nuts have a high nutritive value (39% protein, 50% fat) and occupy an important place in Mediterranean cuisine.

- The cones and the seeds only mature 3 years after pollination. Since antiquity, pine nuts have been considered an aphrodisiac, while the cone has been represented in artworks as a carrier of various symbolic meanings, most often associated with fertility.

Church of the Apparition of the Virgin Mary

In 1700, Bishop Paolo Naldini recorded in his exceptional work Corografia ecclesiastica several places of worship in Strunjan: the large Church of the Virgin Mary and three smaller ones, the Church of St. Christopher, the Church of the Holy Spirit and the Church of St. Bassus. While nowadays only photographic or written references testify to the former existence of the small ones, the church dedicated to the Virgin Mary still reigns from the top of a cliff as the most popular pilgrimage centre in Istria.

The original church stood here as early as 1200. On a map from the Regional Archives of Piran from the period 1200‒1210 there is already a rural settlement marked by the inscription “Planus seu planetus S. Mariae” (On St. Mary’s Plain), which surrounded the church and bore its name. At first, the sanctuary was maintained by the Benedictine sisters from the convent next to the Church of St. Bassus, and upon their departure from the area by the Benedictine fathers from the monastery on the other side of the saltpans, who gathered in this church for prayer whenever they worked in the nearby vineyards.

The first extensive renovation of the building was carried out in 1463, enabled by a generous donation made to the church by Osvalda Petronio Barcazza, a wealthy widow from Piran. The sanctuary was even renamed Barcazza after her for a while. When the Benedictines from the monastery left, the management of the church was assumed by the chapter of Piran.

The legend has it that in 1512 two vineyard guards witnessed the Mother of God appearing on the doorstep of the church and bemoaning its bad state of repair, which supposedly indicated that the congregation had forgotten about her. After that, the building was restored, enlarged and renamed the Church of the Apparition of the Virgin Mary.

The miraculous event which soon turned the sanctuary into the most important Istrian shrine was depicted in 1520 by the painter Francesco Valerio. While his artwork on wood still adorns the main altar, the church walls are covered by ten large canvasses representing scenes from Mary’s life, from birth to glorification, which were commissioned or perhaps even painted by the Piran parish priest Tomaž Gregolin between 1656 and 1671.

In 1907, the Strunjan sanctuary came under the care of the Franciscans from the Italian province of Trento, who had the picture of Our Lady of Mercy, with the permission of Pope Pius X, crowned at the 400th anniversary of the apparition.

In 1955, the building changed hands again and its management was taken over by the Slovene Franciscan province of the Holy Cross. Since 2014, when the Franciscans left the church and town, the Strunjan parish and monastery have been in the charge of the Koper bishopric.

The ample non-material heritage associated with the legend of the apparition, the pilgrimages, processions and miraculous deliverances consists of narratives, memoires and poems and is supplemented by a series of illustrative paintings and ex voto images preserved at the church.

Since recently, the celebration of the event of the apparition has been revived – a procession of boats transporting a statue of the Virgin Mary from Izola to the Strunjan house of God.

The Strunjan Cross

Since 1600, at the edge of the cliff above Moon Bay, rises an imposing stone cross warning the sailors of the proximity of land and marking the location of the Church of the Apparition of the Virgin Mary. Ships travelling past the cross used to sound their horns to greet the Blessed Virgin, and the seafarers would make the sign of the cross and pray to her for their safe return. And according to a legend, the very spot where the cross now stands was the site of a miracle that occurred one far-distant August 15.

A violent storm was raging and the ships at sea would most likely have gone under had not the Virgin Mary appeared above the Bay of St. Cross. The sea instantly calmed, the storm blew over and the sailors were saved. It is said that there are imprints of footsteps and tears in the rock where the Blessed Virgin cried to save the seafarers.

In 1912, when the cross was already in disrepair, the sailors and Franciscan fathers restored it, but only a few years later it surrendered to the strong gusts of the burja (bora) and collapsed. It was subsequently replaced by a larger and sturdier cross, additionally fitted with a pedestal and a fence.

The spot where the cross is provides an excellent belvedere for the coast underlying the cliff. On a bright day, you can admire the entire Gulf of Trieste and even Triglav, the highest Slovene peak.

Cultural and Agricultural Landscapes

The Peninsula of Strunjan is a coastal area that has remained sheltered from intensive urbanisation and industrialisation. The peninsula and the Bay of Strunjan, which opens at the end of the Strunjan Valley and has been partly turned into saltpans, represent an integral landscape unit incorporating elements of both primeval and cultivated environment, a combination of natural features and testimonies of human activity.

Strunjan, the only town on the Slovene coast to have preserved the pattern of scattered settlement, exhibits the typical rural architecture of the late 19th and the early 20th centuries and is composed of several hamlets: Sv. Duh, Baredi, Karbonar, Dobrava, Dolina, Sanguetera, Ronek, Marčane, Borgola and Štancija.

Here, the typical Mediterranean clustered type of settlement never developed. The houses are scattered around terraced slopes, each reigning over its own stretch of land. Examples of farmsteads with the house and outbuildings erected in parallel to save space or nucleated farms are rare and uncharacteristic, for the properties are quite large (around 25 hectares) with the family house usually located centrally.

The most characteristic features of the agricultural landscape of the Koper littoral are cultural terraces, which prevent excessive soil erosion during heavy rainfalls and retain moisture deeper in the soil during summer draughts. Typical of Strunjan are vineyard-crop terraces, orchard-garden terraces and particularly pure garden terraces. The latter are most suitable for growing early vegetables.

The cultivated slopes, converted into terraces, are most often supported by dry-stone walls built without binding agents, which create living spaces for numerous animal species.

For more information on dry-stone construction check the links below.

- Video on dry-stone construction (in Slovene) produced by the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia.

- Dry-stone construction manual (in Slovene and Croatian).

The Golden Apple from the Garden of Trieste

In the beginning of the 20th century, Strunjan was best-known for growing early vegetables and fruits, which were regularly taken by boat to Trieste to be sold at the local market. Strawberries, their aroma pervading the entire Strunjan Valley, were very highly rated, as were cherries, apricots and peaches. Later, the focus of the farmers shifted to olive oil and wine production and the cultivation of artichokes, which are autochthonous to the Istrian coast. For the past decade or so, however, the undisputed king of agriculture of the Peninsula of Strunjan has been the persimmon.

Persimmon or kaki (Diospyros kaki) was introduced to Slovenia from Italy in the years preceding WWII, first in the Primorska region. On the coast it was first planted by Stanislav Knez, whose family is today one of the largest producers of this sweet fruit in Slovenia. Stanislav was an Italian soldier, and when his battalion made a stop in Sicily on the return from Libya, he saw a persimmon plantation for the first time. Upon his arrival home, he borrowed the money from his father to buy the seedlings and in 1939 planted the first persimmon trees in Strunjan.

Until 2001, the large investment into the plantation had brought little return, but Stanislav lived to see the day when the nutritious pome got the appreciation it deserved all around Slovenia. Nowadays, the Strunjan plantations yield one third of all persimmons produced in Slovenia, and in the first days of November, the town traditionally hosts a festival dedicated to this fall fruit.

“Fugitives from Gardens”

For millennia, man has been cultivating plants for his own benefit. After all, this is what enabled our ancestors to settle and start building civilisation. But if people once used to cultivate plants for their own survival and used the species that thrived in their close vicinity, the situation today is much different, as trees, bushes and flowers are often grown for decoration, and the allochthonous species with their exotic beauty sometimes attract us far more than the indigenous ones.

A species transferred from its native distributional range into a completely new environment is called alien. Since it is usually not adapted to new living conditions, it normally cannot survive without man’s help. But if it finds itself in a habitat similar to its original one, it can subsist on its own. There are several species like that in our natural surroundings, but in the case of many of them we do not even realise that they have been brought from elsewhere.

For instance, almost all genuine Mediterranean plant species on the Slovene coast are allochthonous, including the olive tree, bay laurel and pine. The latter has been spread by human activity for so long that its exact origin is nowadays a puzzle. Most plants in our gardens are non-native species, and as for examples from the animal world, everyone has probably heard about the Asian tiger mosquito by now.

Sometimes the alien and the native variety of an organism come in contact in the same environment, in which they also share similar living patterns. When such new species are more aggressive in securing a living space – or, in the case of animals, food – if they propagate more successfully while remaining, as newcomers, without natural enemies, they begin to supplant the indigenous species and change the environment in which they have settled. The shed leaves or branched roots of some plants can alter the pH of the soil, making it more difficult for their neighbours to thrive. Others, the so called pioneer species, are the first to colonise barrens (or disrupted ecosystems caused by forest fires, which are often part of the natural cycle), depriving the autochthonous vegetation of the space to grow. Such plants are called invasive alien species.

What makes the problem even more difficult is that the invasive character of an organism generally cannot be predicted and is only revealed when it is already causing problems in a particular habitat. The majority of invasive alien species have spread accidentally, “fleeing” from our gardens, but some we have released into the environment intentionally, unaware of the damage they could do to the native species and to our natural environs. Such was the case with the red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), a popular terrarium pet. When the owners got tired of keeping these animals, they abandoned them in nearby pools or ponds, sealing the fate of the Slovene indigenous turtle species – the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis) – which the red-eared slider is successfully crowding out of its living space.

To prevent the diffusion of organisms with a destructive effect on biotic diversity, we should, before introducing any exotic animal or plant species into our environs, gather all information on the level of its invasiveness, or, better yet, choose a similar domestic species instead. After all, a plant native to the biota of a specific place is better adapted to it, can most probably survive even extraordinary weather conditions, and in the case of “elopement” or release into the wild does not cause detectable changes in nature.

Much information on exotic plants and animals, the problems they pose and the possibilities of replacing them with similar indigenous varieties is available at a special website dedicated to alien species in Slovenia.

Gifts of the Sea

In the past, the fishing method employed in Strunjan waters was seine fishing with a drag net. In spring, when sardines swam near the shore to spawn, the fishermen would surround them with their boats and beat their feet on the wooden floor of the vessels to scare the sardines into the nets they had deployed from the beach. The work was hard, as the drag net had to be held and hauled by hand. When the noise of the fishermen’s stamping reached the nearby church, its bell was sounded to summon men and children from the fields. In return for their help in dragging the net from the water each of them received a hatful of fish.

Presently, the fishermen operate in the inshore belt of the park a few months a year. With small boats and nets they catch minor quantities or large fish, allowing the fish population the opportunity to increase again during the rest of the year.

In the last decade, six commercial fishermen from the Strunjan boat harbour were allowed to fish in park waters. The dominant species in their catch were sole, cuttlefish, gilt-head bream, European flounder, common pandora, European seabass, red scorpionfish and black mullet. The composition and abundance of fish fauna was different from year to year, but it would be difficult to pinpoint the reason for that based on such a small sample.

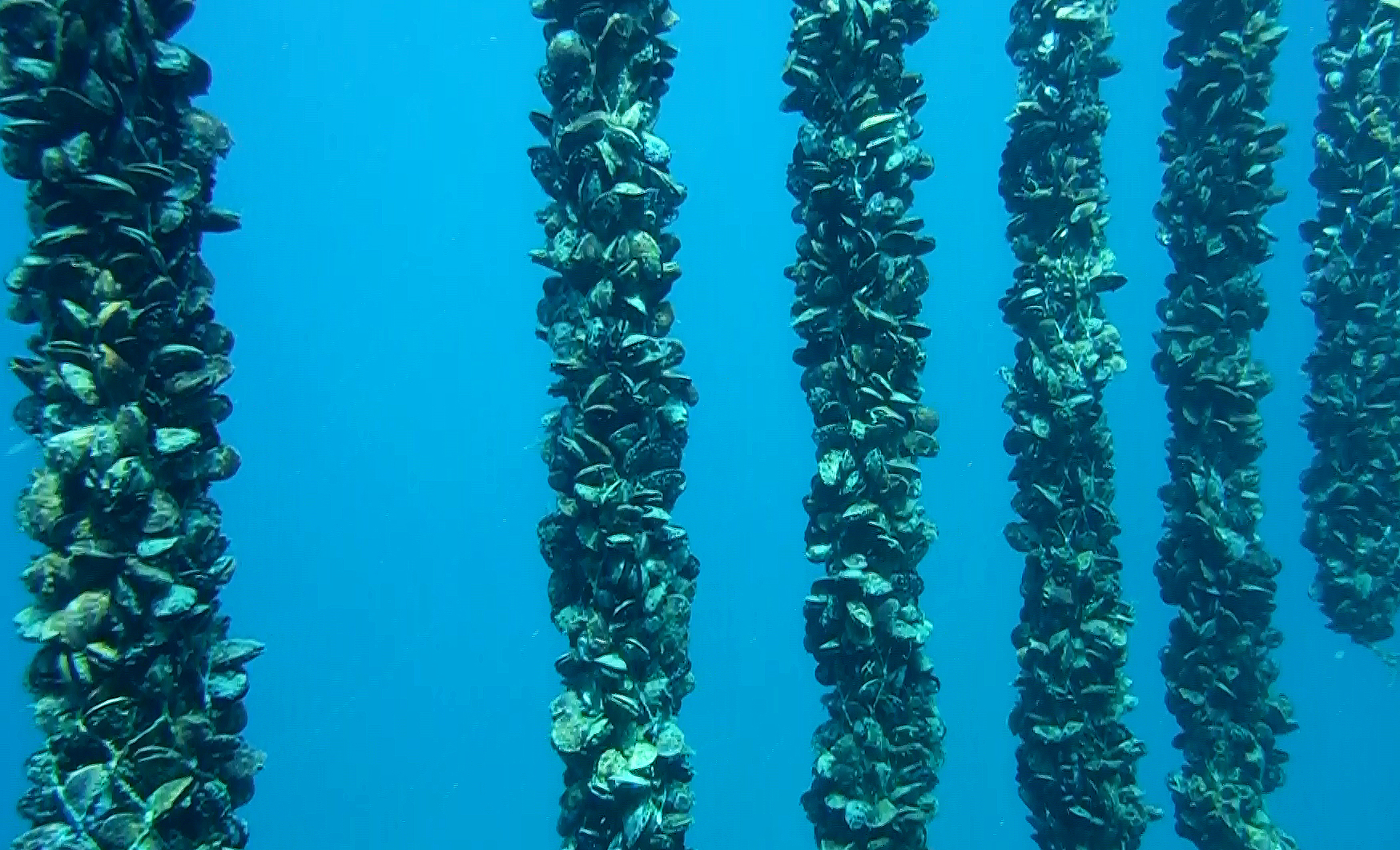

Another source of income for the local people is shellfish farming. Two types of molluscs used to be grown in the area of the reserve and several other species, now protected, were harvested from the park’s waters.

The first shellfish farms in the Bay of Strunjan were set up for the cultivation of European flat oyster (Ostrea edulis), which was appreciated in such a grandiose setting as the Viennese court, but was eventually replaced in the 1970s by the Japanese oyster (Crassostrea gigas) since the latter can grow faster and is able to adapt better to new habitats. In fact, it adjusted so well to our environment that it soon became an invasive marine species in Slovene waters.

The other species of shellfish that was and still is farmed in the Bay of Strunjan, is the Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis). It is known in the Adriatic by more than 30 different names, which testifies to its great importance for the economy of this region. In Europe, the Mediterranean mussel was first mentioned as a species for cultivation as far back as 1235, while mussel farms are said to have been kept even in antiquity.

In 1981, the Municipality of Piran issued a permit for commercial mussel farming in the Bay of Strunjan. Here, the extensive mariculture is conducted without the use of feed, as the mussels get everything they need for their growth and development from the sea water that they filter.

The culture plots extend over a total of 11 hectares, almost the surface area of 15 soccer fields, and yield between 200 and 300 tons of molluscs a year.